How State-Level Incentives Impact Data Center Development

State-level incentives are contributing to the boom in large data center development, but the benefits for local tech job creation remain elusive.

Data centers are the backbone of modern information technology and one of the fastest-growing real estate investment segments in the United States. Although they are now closely associated with large language models (LLMs) and AI, data centers have been central to digital infrastructure for more than two decades. Since the early days of the internet, they have supported the expansion of networks and cloud computing throughout the 2000s and 2010s.

Over the past two decades, U.S. states have enacted legislation offering tax incentives to attract data center development. The goal of these policies is to stimulate local economic and job growth. Many state and local officials view data centers as a catalyst for building a local tech industry.

This approach is not new. Local and federal tax incentive programs have long been used to stimulate investment and job creation in the United States. However, the effectiveness of these programs in attracting new investment activity and generating broader economic spillovers varies considerably. For many initiatives, evidence on their effectiveness remains inconclusive long after they are enacted.

Do state-level tax incentives for data centers meaningfully shape the geography of data center development? Are these programs substantial enough to alter developers’ decisions about where to invest? Do data centers act as catalysts for new tech hubs?

A recent working paper by Antonio Gargano and Marco Giacoletti provides evidence that incentives significantly increase data center development. However, the increase in investment is concentrated primarily in the largest-scale facilities. Tax incentives appear to be contributing to a shift in data center development toward hyperscale, single-tenant cloud facilities. Because of the scale of their operations, each of these projects receives millions of dollars in annual tax benefits that, when capitalized, represent a substantial share of total development costs.

Overall, these incentives meaningfully impact the data center industry and represent a substantial long-term commitment by U.S. states. Yet the paper finds that the effects of data center development on local tech job creation are limited or insignificant.

Given the scale of these policies, regulators should carefully assess their broader economic benefits. For the programs to be justified, their primary gains must extend well beyond local tech employment.

State-Level Incentives Impact Development, but Scale Matters

The paper employs a staggered difference-in-differences (DiD) framework, using recent methodologies that correct for biases in traditional staggered designs. This approach allows the authors to identify the causal effect of incentive implementation on data center development.

Although the first incentive law was enacted in 2000, most programs were introduced during the 2010s. The newest provisions (in Kansas, Massachusetts, and West Virginia) took effect in 2025. These incentives primarily take the form of tax rebates. States do not offer direct subsidies that cover development costs. Instead, the benefits operate indirectly by reducing operating costs for new facilities, thus increasing their valuations, and the value created by new development.

The paper finds sizable effects, but also clear differences across categories of data centers. The analysis focuses on three categories: hyperscale, wholesale, and retail.

Hyperscale data centers are the largest category and began expanding rapidly in the 2010s. Designed for large-scale, high-speed computing, they have become the key infrastructure to modern LLM and AI workloads. In this industry, asset size is measured by the amount of power that can be reliably delivered to servers, which is called Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS). Operating hyperscale facilities in the dataset used in the paper average about 33 megawatts of UPS. Wholesale data centers fall in the intermediate range and support either cloud computing or network infrastructure. Retail data centers are the smallest category, averaging roughly 4 megawatts of UPS, and focus on network connectivity and server colocation.

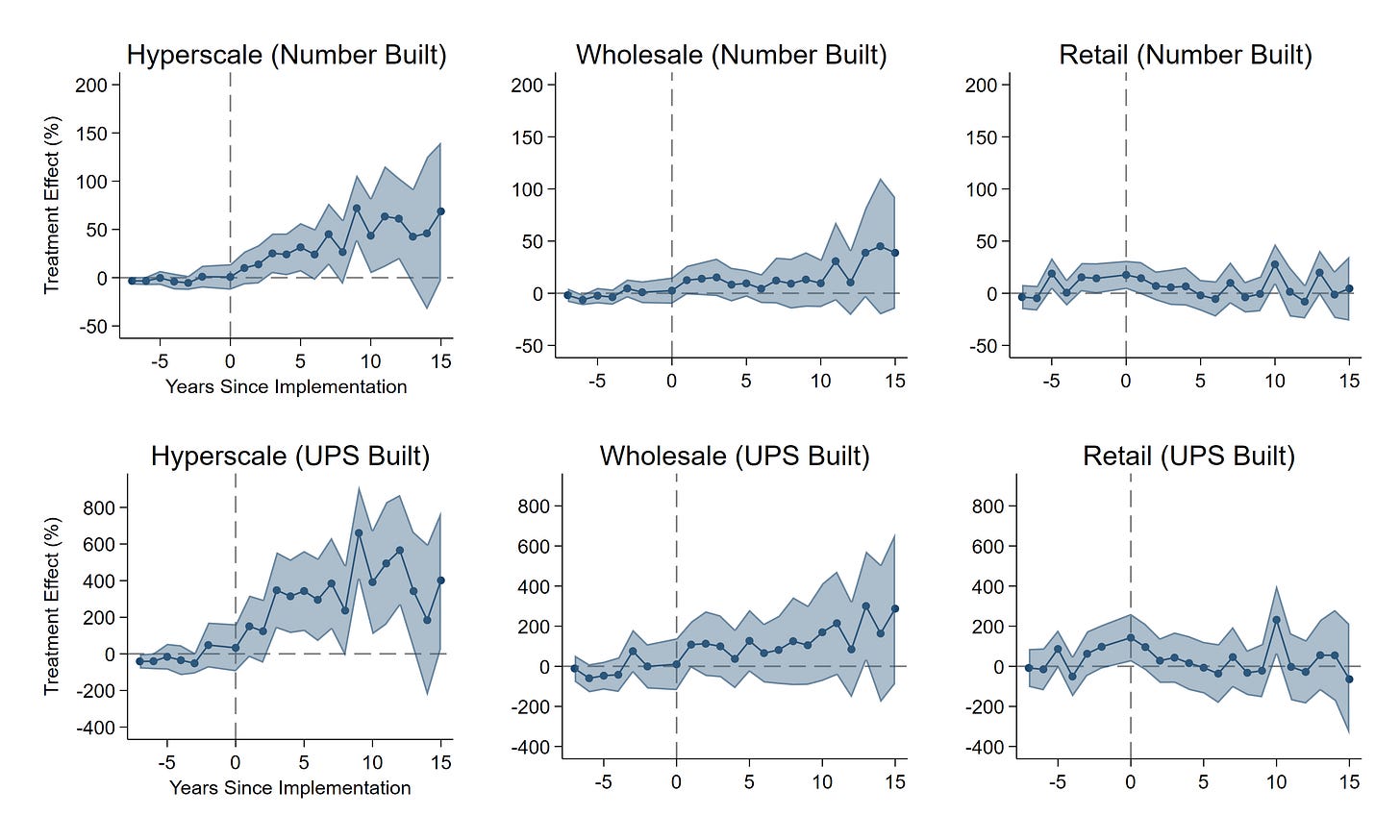

The event-study chart below shows the average effect of implementing a state-level incentive package on the development of new data centers across categories. On the x-axis, 0 denotes the year in which the incentive was enacted; positive values represent years after implementation, and negative values represent years before.

The results show very large effects on hyperscale development: within five years of implementation, the number of new hyperscale facilities increases by more than 50%, and their total combined UPS capacity increases by over 200%. Wholesale data centers also exhibit positive responses, though the estimated effects are smaller and substantially noisier. There is virtually no detectable impact on the development of retail data centers.

The analysis in the paper shows that this pattern is largely driven by the design of state incentive laws, which impose minimum size thresholds to qualify for incentives. These thresholds fall well within the operating scale of hyperscale, high–computing-power facilities but exceed the typical size of retail, network-oriented data centers. As a result, hyperscale projects are the most likely to be eligible for incentives, while most development projects for retail facilities are effectively excluded.

Incentives Create Substantial Value for Developers and Operators

Most states structure their incentives as sales and use tax exemptions, with a smaller number also offering property tax abatements. Sales and use tax exemptions typically cover electricity consumption as well as purchases of tangible equipment (servers, storage devices, and networking hardware), and key infrastructure components (electrical systems, UPS capacity, and cooling equipment). As noted earlier, these incentives indirectly stimulate data center investment by improving operating margins and increasing the value of new facilities.

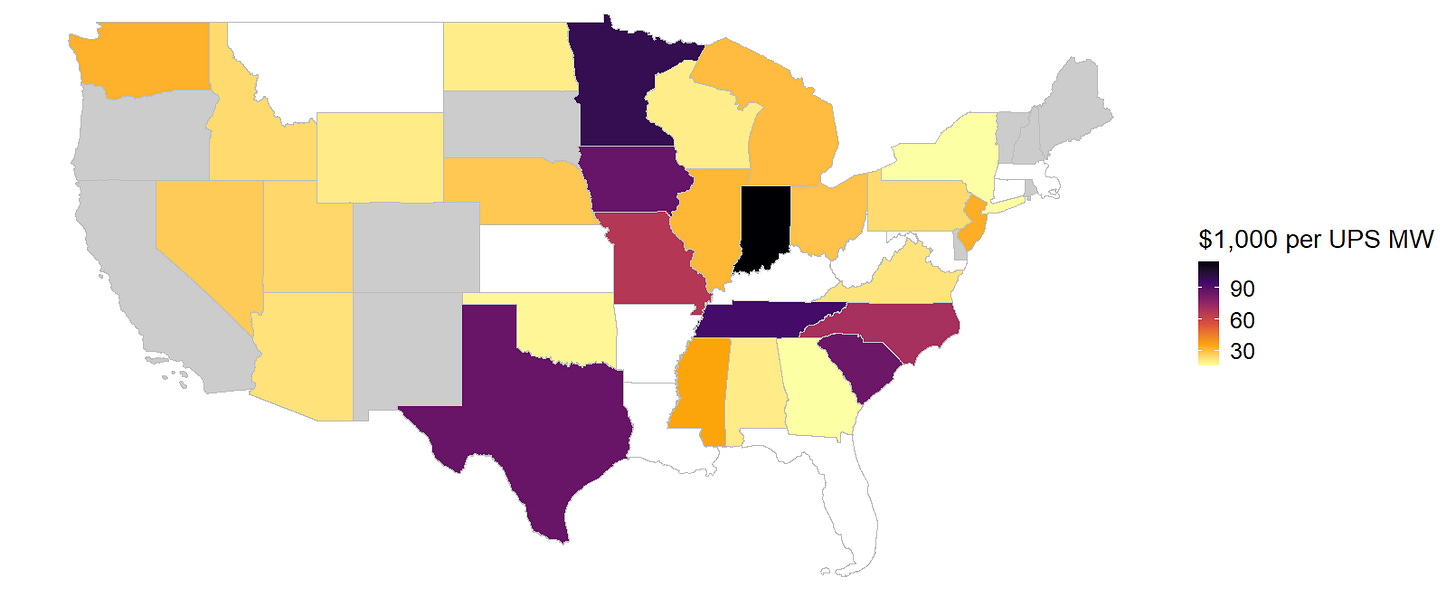

How much value do these incentives deliver to newly developed facilities? The paper addresses this by estimating sales and use tax rebates for data centers operating in 2025. The figure below reports incentives per megawatt of UPS capacity. States shown in white have active incentive programs but no qualifying data centers in the paper’s dataset, while states in grey do not offer incentives. Alaska and Hawaii are omitted because neither state has an incentive program.

Although Virginia hosts the largest concentration of data centers in the country, it does not offer the highest subsidy per unit of power; its incentives amount to only about $22,000 per UPS megawatt, across qualifying operating facilities in 2025. Indiana, Minnesota, and Tennessee provide the most generous benefits. Texas, Iowa, and South Carolina also provide substantial incentives to qualifying facilities in 2025, each exceeding $80,000 per UPS megawatt.

The average operational hyperscale data center covered by the study has 33 megawatts of UPS capacity. With incentives of $80,000 per UPS megawatt, this translates into approximately $2.64 million in annual operating expense savings in 2025.

In commercial real estate, a common back-of-the-envelope valuation approach divides net operating income by prevailing market cap rates to find a rough estimate of property values. Using a current hyperscale cap rate of roughly 6.5%, these annual savings capitalize to about $40.6 million in additional asset value for a typical 33 megawatt facility.

Local Long-Term Effects on the Tech Job Market are Not Significant

Finally, the paper examines the effects of data center development on local labor markets, with a particular focus on the creation of new tech jobs. While the construction of data centers can generate short-term employment gains in the construction sector, and may temporarily stimulate local economic activity, these benefits are transient.

The incentives are structured as long-term tax rebates: they reduce operating costs for decades. This is capitalized into substantial increases in asset values. Thus, long-term creation of high-paying jobs appears to be a natural metric for evaluating the local economic benefits of these programs. Moreover, policymakers have argued that attracting large data center projects can serve as a catalyst for expanding the state’s broader tech sector.

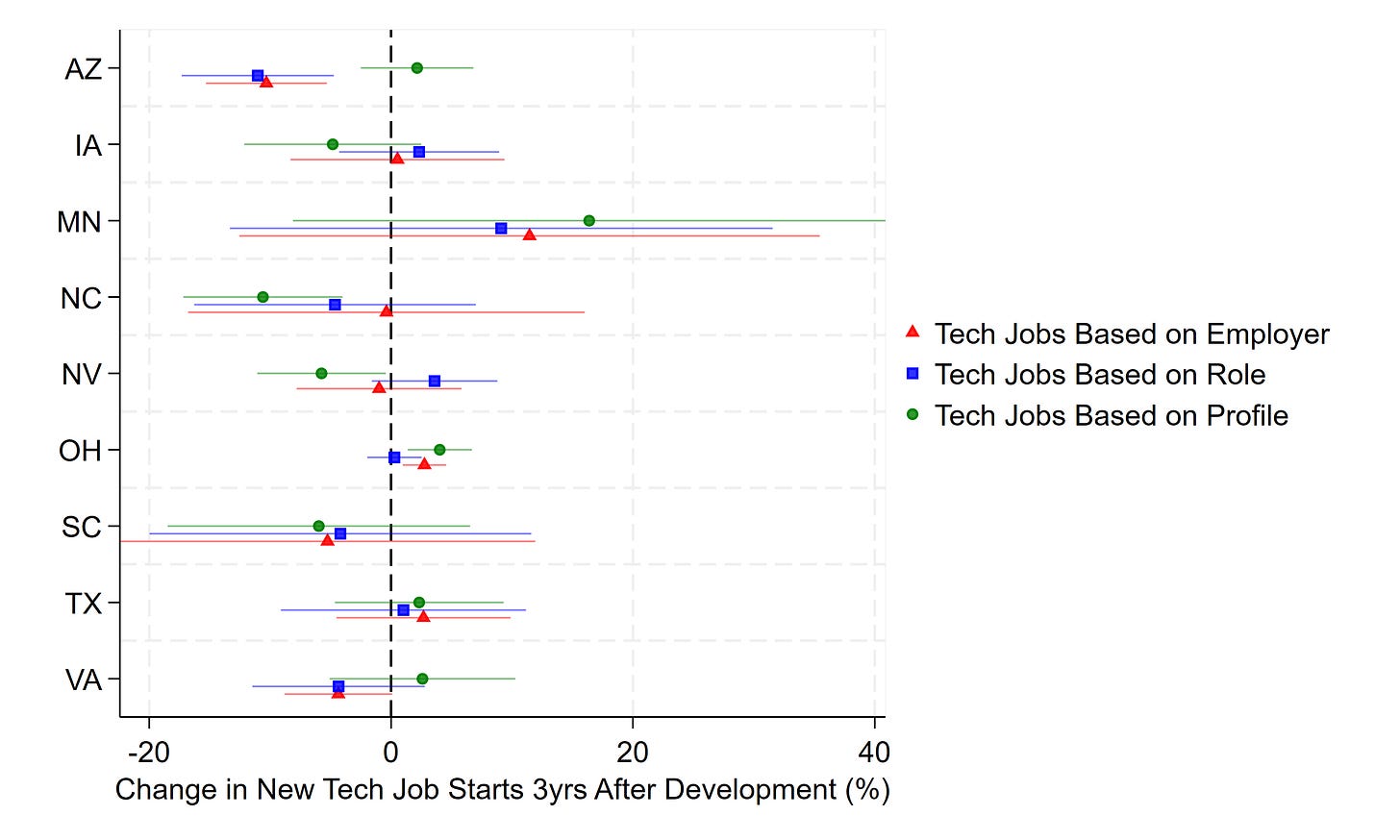

Does data center development lead to an increase in new tech jobs? To answer this question, the paper uses new data from RevelioLab, which compiles individual job profiles from online sources and links them to specific employers and locations. Using these data, the authors construct three measures of annual tech job creation at the census place (city, town, or unincorporated area) level. The first measure identifies tech jobs based on profile text descriptions, the second one is based on standardized occupational classifications provided by RevelioLab, and the third one uses employer characteristics.

Because the location of data centers within a state is not random, the paper employs a matching estimator to ensure that census places exposed to new data center development are compared to similar places that are not. The matching procedure aligns locations on key demographic and economic characteristics.

The figure below reports the estimated effect of developing a new data center within 10 miles of a census place on the relative increase in the number of new tech jobs initiated in that same place three years later. Dots of different shapes correspond to point estimates for different measures of new tech jobs, while the solid lines represent confidence intervals.

Results are shown for Arizona, Iowa, Minnesota, North Carolina, Nevada, Ohio, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia. These states have both substantial incentive programs and a significant amount of large-scale data center development over the past 15 years.

The results do not provide consistent evidence of positive effects. Instead, the estimates are either close to zero or extremely noisy. Similar patterns emerge across alternative time horizons and when varying the matching procedure. The only state showing systematically positive and significant impacts is Ohio, but even there the estimated effects are modest, on the order of a 1%–5% increase in new tech job starts. For census places that experience data center development, the average number of annual tech job starts in Ohio is about 150, so a 1%–5% increase translates into only 2 to 7 additional jobs per year.